* Move workspace members to have zebra- names. This commit breaks the build because it doesn't update any of the Cargo.toml files, but the advantage is that this commit is a simple git mv for ease of review. * Update Cargo.toml files to have new file paths. This is a separate commit to the preceding commit for ease of review (so that the preceding commit is a simple git mv). |

||

|---|---|---|

| .. | ||

| src | ||

| Cargo.toml | ||

| README.md | ||

README.md

Chain

In this crate, you will find the structures and functions that make up the blockchain, Bitcoin's core data structure.

Conceptual Overview

Here we will dive deep into how the blockchain is created, organized, etc. as a preface for understanding the code in this crate.

We will cover the following concepts:

- Blockchain

- Block

- Block Header

- Merkle Tree

- Transaction

- Witnesses and SegWit

- Coinbase

Blockchain

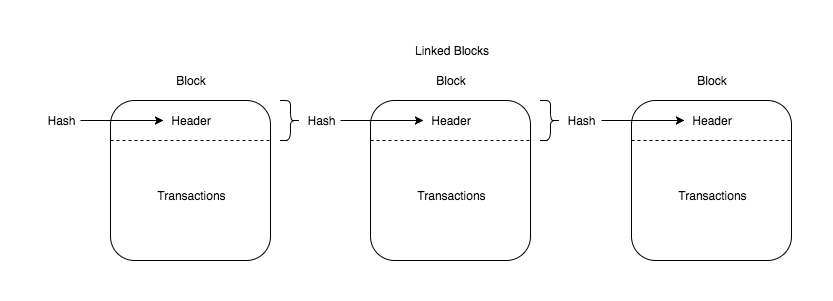

So what is a blockchain? A blockchain is a chain of blocks...

Yep, actually.

Block

The real question is, what is a block?

A block is a data structure with two fields:

- Block header: a data structure containing the block's metadata

- Transactions: an array (vector in rust) of transactions

Block Header

So what is a block header?

A block header is a data structure with the following fields:

- Version: indicates which set of block validation rules to follow

- Previous Header Hash: a reference to the parent/previous block in the blockchain

- Merkle Root Hash: a hash (root hash) of the merkle tree data structure containing a block's transactions

- Time: a timestamp (seconds from Unix Epoch)

- Bits: aka the difficulty target for this block

- Nonce: value used in proof-of-work

How are blocks chained together? They are chained together via the backwards reference (previous header hash) present in the block header. Each block points backwards to its parent, all the way back to the genesis block (the first block in the Bitcoin blockchain that is hard coded into all clients).

Merkle Root

What is a Merkle Root? A merkle root is the root of a merkle tree. As best stated in Mastering Bitcoin:

A merkle tree, also known as a binary hash tree, is a data structure used for efficiently summarizing and verifying the integrity of large sets of data.

In a merkle tree, all the data, in this case transactions, are leaves in the tree. Each of these is hashed and concatenated with its sibling... all the way up the tree until you are left with a single root hash (the merkle root hash).

Transaction

According to Mastering Bitcoin :

Transactions are the most important part of the bitcoin system. Everything else in bitcoin is designed to ensure that transactions can created, propagated on the network, validated, and finally added to the global ledger of transactions (the blockchain).

At its most basic level, a transaction is an encoded data structure that facilitates the transfer of value between two public key addresses on the Bitcoin blockchain.

The most fundamental building block of a transaction is a transaction output -- the bitcoin you own in your "wallet" is in fact a subset of unspent transaction outputs or UTXO's of the global UTXO set. UTXOs are indivisible, discrete units of value which can only be consumed in their entirety. Thus, if I want to send you 1 BTC and I only own one UTXO worth 2 BTC, I would construct a transaction that spends my UTXO and sends 1 BTC to you and 1 BTC back to me (just like receiving change).

Transaction Output: transaction outputs have two fields:

- value: the value of a transaction

- scriptPubKey (aka locking script or witness script): conditions required to unlock (spend) a transaction value

Transaction Input: transaction inputs have four fields:

- previous output: the previous output transaction reference, as an OutPoint structure (see below)

- scriptSig: a script satisfying the conditions set on the UTXO (BIP16)

- scriptWitness: a script satisfying the conditions set on the UTXO (BIP141)

- sequence number: transaction version as defined by the sender. Intended for "replacement" of transactions when information is updated before inclusion into a block.

Outpoint:

- hash: references the transaction that contains the UTXO being spent

- index: identifies which UTXO from that transaction is referenced

Transaction Version: the version of the data formatting

Transaction Locktime: this specifies either a block number or a unix time at which this transaction is valid

Transaction Fee: A transaction's input value must equal the transaction's output value or else the transaction is invalid. The difference between these two values is the transaction fee, a fee paid to the miner who includes this transaction in his/her block.

Witnesses and SegWit

Preface: here I will try to give the minimal context surrounding segwit as is necessary to understand why witnesses exist in terms of blocks, block headers, and transactions.

SegWit is defined in BIP141.

A witness is defined as:

The witness is a serialization of all witness data of the transaction.

Most importantly:

Witness data is NOT script.

Thus:

A non-witness program (defined hereinafter) txin MUST be associated with an empty witness field, represented by a 0x00. If all txins are not witness program, a transaction's wtxid is equal to its txid.

Regular Transaction Id vs. Witness Transaction Id

- Regular transaction id:

[nVersion][txins][txouts][nLockTime] - Witness transaction id:

[nVersion][marker][flag][txins][txouts][witness][nLockTime]

A witness root hash is calculated with all those wtxid as leaves, in a way similar to the hashMerkleRoot in the block header.

In the transaction, there are two different script fields:

- script_sig: original/old signature script (BIP16/P2SH)

- script_witness: witness script

Depending on the content of these two fields and the scriptPubKey, witness validation logic may be triggered. Here are the two cases (note these definitions are straight from the BIP so may be quite dense):

-

Native witness program: a scriptPubKey that is exactly a push of a version byte, plus a push of a witness program. The scriptSig must be exactly empty or validation fails.

-

P2SH witness program: a scriptPubKey is a P2SH script, and the BIP16 redeemScript pushed in the scriptSig is exactly a push of a version byte plus a push of a witness program. The scriptSig must be exactly a push of the BIP16 redeemScript or validation fails.

Here are the nitty gritty details of how witnesses and scripts work together -- this goes into the fine details of how the above situations are implemented.

Here are a couple StackOverflow Questions/Answers that help clarify some of the above information:

- What's the purpose of ScriptSig in a SegWit transaction?

- Can old wallets redeem segwit outputs it receives? If so how?

Coinbase

Whenever a miner mines a block, it includes a special transaction called a coinbase transaction. This transaction has no inputs and creates X bitcoins equal to the current block reward (at this time 12.5) which are awarded to the miner of the block. Read more about the coinbase transaction here.

Need a more visual demonstration of the above information? Check out this awesome website.

Crate Dependencies

1. rustc-hex:

Serialization and deserialization support from hexadecimal strings.

One thing to note: This crate is deprecated in favor of serde. No new feature development will happen in this crate, although bug fixes proposed through PRs will still be merged. It is very highly recommended by the Rust Library Team that you use serde, not this crate.

2. heapsize:

infrastructure for measuring the total runtime size of an object on the heap

3. Crates from within the Parity Bitcoin Repo:

- bitcrypto (crypto)

- primitives

- serialization

- serialization_derive

Crate Content

Block (block.rs)

A relatively straight forward implementation of the data structure described above. A block is a rust struct. It implements the following traits:

From<&'static str>: this trait takes in a string and outputs ablock. It is implemented via thefromfunction which deserializes the received string into ablockdata structure. Read more about serialization here (in the context of transactions).

The block has a few methods of its own. The entirety of these are simple getter methods.

Block Header (block_header.rs)

A relatively straight forward implementation of the data structure described above. A block header is a rust struct. It implements the following traits:

From<&'static str>: this trait takes in a string and outputs ablock. It is implemented via thefromfunction which deserializes the received string into ablockdata structure. Read more about serialization here (in the context of transactions).fmt::Debug: this trait formats theblock headerstruct for pretty printing the debug context -- ie it allows the programmer to print out the context of the struct in a way that makes it easier to debug. Once this trait is implemented, you can do:

println!("{:?}", some_block_header);

Which will print out:

Block Header {

version: VERSION_VALUE,

previous_header_hash: PREVIOUS_HASH_HEADER_VALUE,

merkle_root_hash: MERKLE_ROOT_HASH_VALUE,

time: TIME_VALUE,

bits: BITS_VALUE,

nonce: NONCE_VALUE,

}

The block header only has a single method of its own, the hash method that returns a hash of itself.

Constants (constants.rs)

There are a few constants included in this crate. Since these are nicely documented, documenting them here would be redundant. Here you can read more about constants in rust.

Read and Hash (read_and_hash.rs)

This is a small file that deals with the reading and hashing of serialized data, utilizing a few nifty rust features.

First, a HashedData struct is defined over a generic T. Generics in rust work in a similar way to generics in other languages. If you need to brush up on generics, read here. This data structure stores the data for a hashed value along with the size (length of the hash in bytes) and the original hash.

Next the ReadAndHash trait is defined. Traits in rust define abstract behaviors that can be shared between many different types. For example, let's say I am writing some code about food. To do this, I might want to create an Eatable trait that has a method eat describing how to eat this food (borrowing an example from the New Rustacean podcast). To do this, I would define the trait as follows:

pub trait Eatable {

fn eat(&self) -> String;

}

Here I have defined a trait along with a method signature that must be implemented by any type that implements this trait. For example, let's say I define a candy type that is eatable:

struct Candy {

flavor: String,

}

impl Eatable for Candy {

fn eat(&self) -> String {

format!("Unwrap candy and munch on that {} goodness.", &self.flavor)

}

}

// Create candy and eat it

let candy = Candy { flavor: chocolate };

prinln!("{}", candy.eat()); // "Unwrap candy and munch on that chocolate goodness."

Now let's take this one step further. Let's say we want to recreate Eatable so that the eat function returns a Compost type with generic T where presumably T is some type that is Compostable (another trait). Now here, it is important that we only return Compostable types because only Compostable foods can be made into Compost. Thus, we can recreate the Eatable trait, this time limiting what types can implement it to those that also implement the Compostable trait using the where keyword (note this is called a bounded trait):

pub trait Eatable {

fn eat<T>(&self) -> Compost<T> where T: Compostable;

}

pub trait Compostable {} // Here Compostable is a marker trait

struct Compost<T> {

compostable_food: T,

}

impl<T> Compost<t> {

fn celebrate() {

println!("Thank you for saving the earth!");

}

}

So, let's now redefine Candy:

struct Candy {

flavor: String,

}

impl Compostable for Candy {}

impl Eatable for Candy {

fn eat<T>(&self) -> Compost<T> where T: Compostable{

Compost { compostable_food: format("A {} candy", &self.flavor) }

}

}

// Create candy and eat it

let candy = Candy { flavor: chocolate };

let compost = candy.eat();

compost.celebrate(); // "Thank you for saving the earth!"

If this example doesn't quite make sense, I recommend checking out the traits chapter in the Rust Book.

Now that you understand traits, generics, and bounded traits, let's get back to ReadAndHash. This is a trait that implements a read_and_hash<T> method where T is Deserializable, hence it can be deserialized (which as you might guess is important since the input here is a serialized string). The output of this method is a Result (unfamiliar with Results in rust... read more here) returning the HashedData type described above.

Finally, the ReadAndHash trait is implemented for the Reader type. You can read more about the Reader type in the serialization crate.

Transaction (transaction.rs)

As described above, there are four structs related to transactions defined in this file:

- OutPoint

- TransactionInput

- TransactionOutput

- Transaction

The implementations of these are pretty straight forward -- a majority of the defined methods are getters and each of these structs implements the Serializable and Deserializable traits.

A few things to note:

- The

HeapSizeOftrait is implemented forTransactionInput,TransactionOutput, andTransaction. It has the methodheap_size_of_childrenwhich calculates and returns the heap sizes of various struct fields. - The

total_spendsmethod onTransactioncalculates the sum of all the outputs in a transaction.

Merkle Root (merkle_root.rs)

The main function in this file is the function that calculates the merkle root (a filed on the block header struct). This function has two helper functions:

- concat: takes two values and returns the concatenation of the two hashed values (512 bit)

- merkle_root_hash: hashes the 512 bit hash of two concatenated values

Using these two functions, the merkle root function takes a vector of values and calculates the merkle root row-by-row (a row being the level of a binary tree). Note, if there is an uneven number of values in the vector, the last value will be duplicated to create a full tree.

Indexed

There are indexed equivalents of block, block header, and transaction:

- indexed_block.rs

- indexed_header.rs

- indexed_transaction.rs

These are essentially wrappers around the "raw" data structures with the following:

- methods to convert to and from the raw data structures (i.e. block <-> indexed_block)

- an equivalence method to compare equality against other indexed structures (specifically the PartialEq trait)

- a deserialize method